Telecom retirees answer call of history, preserve important artifacts

by Phil Burgess, Unabridged from the Life section of the Annapolis Capital, Sunday May 13, 2019

Unabridged from my weekly Bonus Years column the Life section of the Annapolis Capital, Sunday, May 12, 2019

For nearly four years, beginning in 2005, I had the privilege of working as senior executive in the largest telecommunications company in a nation not my own. That company was Telstra, Australia’s telecommunications giant, which also owned 50 percent of the nation’s cable television network and satellite communications.

During these years, my responsibilities included everything from government affairs and media relations to the company’s foundation and corporate social responsibility programs.

While wearing my foundation and CSR hats, I came to know Brian Mullins, a retired Telstra alum who began his career as a “telegram boy” and later earned the distinction of graduating from the last class to teach the Morse Code of dots and dashes used on the old telegraph machines.

Because of its vast distances (Australia is as large as our own Lower 48), much of it unsettled (with only 24 million people, only slightly more than greater Los Angeles) Australia was perhaps the last developed nation to depend heavily on the telegraph to connect all the nation’s remote towns and small communities. But as the years passed, nearly everyone had a telephone. So, in the early 1960s, as new technology challenged Mullins’ skills as a Morse Codian (as they were called), he was also preparing to retire.

I came to know Mullins because his retirement project – and his passion – was to build and expand a museum devoted to preserving the history of telecommunications in Australia – and to educating younger generations about how copper wires were used to build a nation as communications evolved from Aboriginal message sticks and the semaphore to the Internet.

I took great interest in Mullins’ project and supported him in every way I could. The telecom museum was more than a project. It was and remains his passion.

Perhaps a better word is the Japanese word ikigai (pronounced “iki-guy”), which translates as “a reason for being” or “a sense of purpose or meaning.” Mullins, I think, would say it means “A reason to get up in the morning.”

One of my most memorable experiences in Australia was attending the annual meeting of the Morse Codians in Sydney. Following a luncheon, the officers sat at the head table to call the meeting to order. First, the gavel came down. That stopped the chatter, and the 50 or so in attendance shifted their attention to the front of the room.

Then, the president tapped the microphone with dots and dashes. After a few seconds, everyone laughed. I later learned he had welcomed everyone and then offered a quip – all in Morse Code!

Nearly everyone laughed, but a couple of guys at my table didn’t laugh. One turned to the other and said, mischievously, “Ol’ Stanley never could tell a joke.”

Last week, I received an email about the museum where the artifacts collected by Mullins and his retired band of brothers (and sisters) were recently valued at a staggering $20 million.

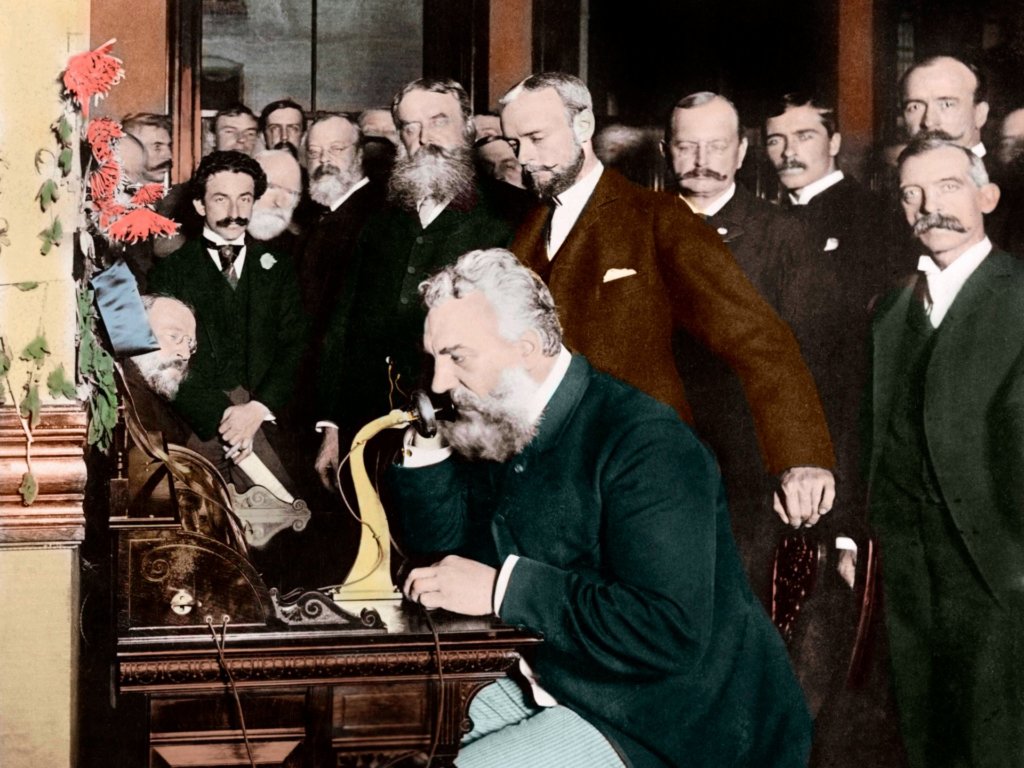

Mullins and his fellow retirees built an enviable hands-on museum with many artifacts that are central to Australia’s national story. Many are items only those in their bonus years would remember – including displays of Morse telegraphy equipment, telephones – early to modern, public “pay phones” (who remembers those?), mobile telephones (the early ones a big as a brick), electromechanical exchange equipment, the original “speaking clock” for the visually impaired, manual switchboards like the one “Ernestine” (a.k.a Lily) Tomlin used on Laugh-In. And there is more modern equipment, such as Internet modems and WiFi, invented by Australian John O’Sullivan.

Another member of the group, Telstra legal counsel David Field, is a photography buff. Several years ago he started a project to photograph heritage telco equipment. In writing about his experience, he shared interesting observations that include lessons for us today.

In writing about an old exchange in western Sydney, he noted the large size of the switching equipment inside the exchange and the sheer volume of wire linking copper cables under the surrounding streets.

“There was a pair of copper wires for every telephone subscriber…hundreds

of thousands of wires. Kilometers of wire built up over decades…tons of it just

in this one exchange.”

He continued with an observation that caught my eye.

“A physical copper connection to the outside world requires the

work of human hands…Behind all this were countless hours of human effort built

up over hundreds of careers, so that everyone can be connected. So that everyone

can talk to their grandkids, ring about a job, talk to a customer, order a

pizza…so that the rest of the community could be connected.”

Field continued, “A friend of mine describes the work of connecting people as

more than a job, he describes it as a “calling”. Something

bigger and more important than just a way to get paid, a “calling” is

something with a higher purpose that has to be done.”

He added, “That might be a bit old-fashioned, but even today the work of connecting people is vital to the community…it is rare to see such a compelling visual demonstration of how much effort, by how many people, over how many years, has gone into keeping the community connected. Yet what I was seeing was just the tiniest tip of the iceberg in relation to everything that needs to happen before anyone can pick-up a phone.”

“This [photography] project is about stopping to think about the people who’ve spent their careers working to connect the rest of us.”

It’s amazing what a few retired people with a vision and a commitment to execute can achieve – and it was all accomplished by retired volunteers who had found a cause: to preserve a multi-generations national treasure.

With rapidly changing technologies uprooting existing institutions and existing ways of doing things, there are increasing opportunities to preserve for future generations the artifacts and practices that made America the envy of the world – a challenge that can be answered by a growing number of retirees with energy, connections and know-how to preserve for future generations the best of days gone by.

Get the Bonus Years column right to your inbox

We take your inbox seriously. No ads. No appeals. No spam. We provide — and seek from you — original and curated items that make life in the Bonus Years easier to understand and easier to navigate.