There are many ways to make your mark, even in the bonus years

by Phil Burgess, Unabridged from the Life section of the Annapolis Capital, Sunday March 31, 2013

The psychologist Carl Jung wrote, “A human being would certainly not grow to be seventy or eighty years old if this longevity had no meaning for the species.” He goes on to say, “The afternoon of life must have a significance of its own and cannot be merely a pitiful appendage of life’s morning.”

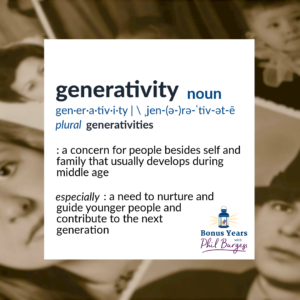

For many of us, that unique significance of later-life is what another psychologist, Erik Erikson, called “generativity” – which includes the desire to nurture and guide younger people and thereby contribute to the next generation.

When I talk to people about their bonus years’ aspirations, I often hear expressions of generativity, especially from grandparents. In fact, most grandparents I’ve interviewed are deeply engaged with their grandchildren, consciously trying to shape the knowledge, attitudes and practices of the offspring of their own children.

Generativity is expressed in many ways. Some prepare a family tree to inform the younger generation. Others write their autobiography so kids can better understand the forces that shaped the lives of their parents and grandparents. Still others serve younger people as mentors and coaches.

I was on the receiving end of grandparents who had a huge impact on me. Just last week, I was reminded of a life lesson I learned from my maternal grandfather who, I’m sure, never heard the word “generativity.” However, looking back, I know he was quite intentional about teaching worldly virtues to me and my cousins.

My grandfather lived in Valparaiso, Indiana, a mid-sized town southeast of Chicago, where he owned an appliance store. He sold everything from refrigerators and “ranges” to fans and water heaters – even radios for the kids who went to Valparaiso University just down the street. If it ran on electricity or natural gas, he sold it.

I loved spending time with my grandfather, especially in his store, where he would put me to work. There wasn’t a dull moment. I was either doing light work like sweeping, dusting or polishing or heavy stuff like uncrating new merchandise or helping to load a delivery truck. He would also let me listen in as he pitched a customer on a new four-burner range or the wonders of an ice-making refrigerator. Each night he would tell me stories as we counted the money before leaving it off at the bank in a special deposit bag.

I went up to Valpo (as we called it) every summer for a month – starting when I was 10. I worked in the store every day, beginning at 7:00 am and often as late as 7:00 pm. After a couple of years, when my grandfather had to leave the store for a service call or to run an errand, he would leave me “in charge” – usually for 30-60 minutes, and never more than two hours. When he left, his last words would be, “I’m leaving now. You mind the store, y’hear!” “Yes sir,” I always answered.

“Mind the store” was a new expression to me. I had never heard it before (and not much since, for that matter). But it was an expression my grandfather used a lot – and I quickly learned what it meant the first time he left me in charge. The learning experience went something like this.

When he returned from the errand, he said, “How’d it go, son?” “No problems,” I said. “Mrs. Snyder came in to pay down their credit account (this was before credit cards), and some people came in to look at refrigerators.”

“Good,” he said, adding, “But it sounds like you had a lot of time on your hands. Right?” “Right,” I responded. That response created the teachable moment as my grandfather asked, “Why then hasn’t the waste basket been emptied. The glass on the front door still has finger prints and hand prints. The refrigerators and stoves have not been polished. Why not?”

When I reminded him I had not been asked to do those chores, he reminded me that he asked me to mind the store and that I had said I would.

That’s when I learned that to mind the store meant to “look after things” – and not just in a reactive sense but in a proactive sense. Minding the store meant to find things that needed to be done – to wash a window, replace a price tag that had fallen off, uncrate a new range that had just arrived in the back room. Minding the store is a proactive concept that means “be alert to anything that needs to be done – and do it!” It’s a call to action.

The habit of “minding the store,” learned that summer as I worked alongside my grandfather, became an integral part of my life. When I became a father, I translated that lesson to my own children. From a very young age I encouraged them always to “put your hand up” whenever presented with an opportunity – and to “hone your peripheral vision” so as not to miss any opportunities to help out or try something new.

So, when people address the need to leave a legacy and then start talking about “big things” like buildings, books and treasure, I think of minding the store – a life lesson learned a from a grandfather who cared enough to teach, trust and spend time with a twelve-year-old youngster and, in the process, leave a legacy that continues with great grandchildren he never knew.

Get the Bonus Years column right to your inbox

We take your inbox seriously. No ads. No appeals. No spam. We provide — and seek from you — original and curated items that make life in the Bonus Years easier to understand and easier to navigate.