Berkman’s “lifequake” sent him on a mission to end prison slavery

by Phil Burgess, Unabridged from the Life section of the Annapolis Capital, Sunday November 15, 2020

Just when everything seems to be going smoothly, life sometimes hits you in the head with a brick: cancer, a heart attack or other life-threatening illness; the loss of a loved one; a business failure or financial crisis; a physical disability, depression or other mental health challenge. Most of us have had our share of brick-like disruptions.

In his new book, Life is in the Transitions (Penguin 2020), best-selling author Bruce Feiler calls these big disruptions “lifequakes” – disruptions that change the very trajectory of our life.

Though lifequakes happen at every stage of life – typically every 10 years or so, according to Feiler – they are often most pronounced when they happen during the bonus years. That’s when new realities are more frequent but our physical, financial and spiritual capacity to adapt is often more limited.

Still, for many, even debilitating lifequakes can inspire a new and uplifting trajectory.

During recent weeks of travel, I met many new and interesting people, some of whom were dealing with disruptions and lifequakes.

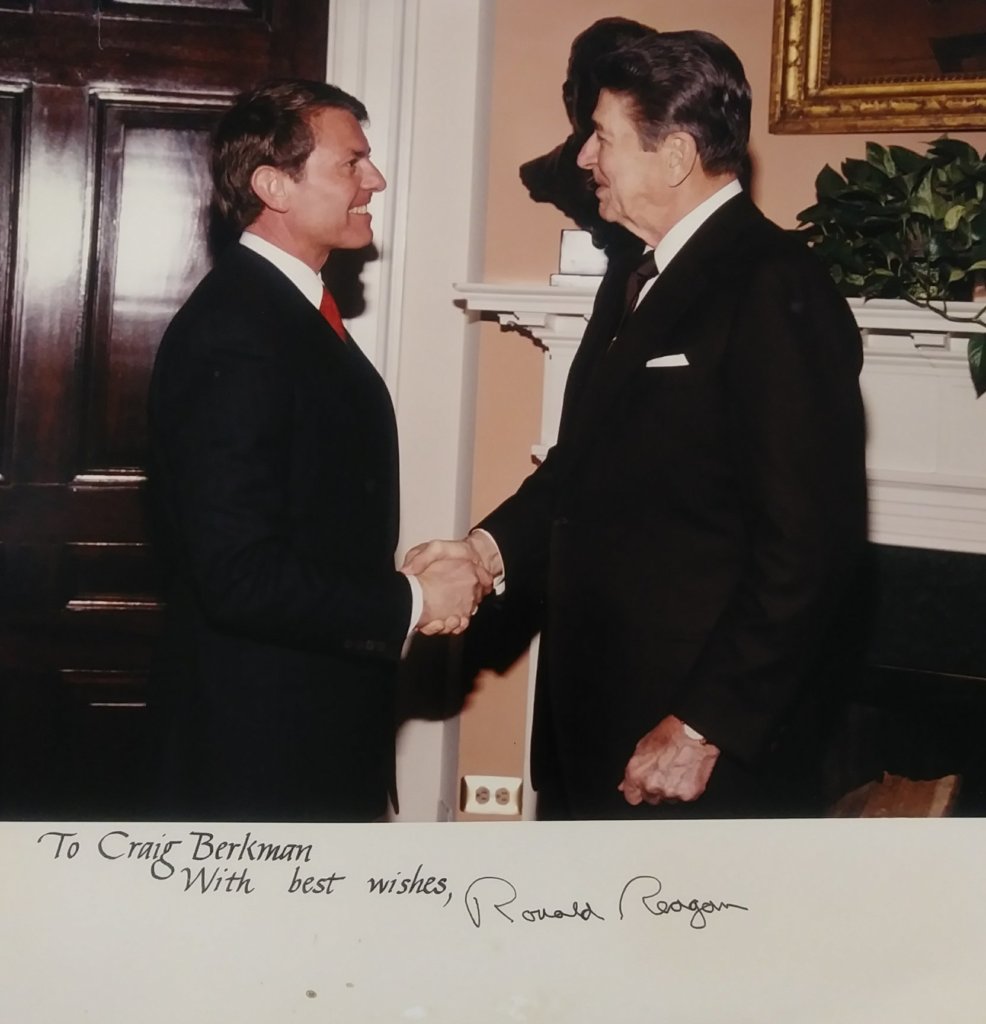

The most fascinating was Craig Berkman, age 79, and a lifelong Oregonian currently living in a suburb of Tampa, Florida. Like many others, Berkman’s lifequake gave sharp redefinition to his life’s trajectory and purpose.

Berkman received his undergraduate degree from Wheaton College (Illinois) in 1963 and a master’s degree in public administration from the University of California (Berkeley) in 1967.

After completing his Vietnam-era military obligation (earning the Joint Services Commendation Medal for meritorious service), he returned to Oregon to attend Portland’s Lewis and Clark law school, earning his juris doctor in 1974.

With those credentials, you would think he had it made. Well, he did.

His first major venture was in 1967. Berkman was a co-founder and original seed investor in Applied Materials, Inc., now the nation’s leading manufacturer of equipment for producing computer chips, flat panel screens, and solar energy devices. AMAT now has a market value north of $60 billion and is ranked #182 on Forbes magazine list of America’s largest companies.

The following year, Berkman left AMAT, devoting most of the next 50 years to philanthropy, community service, and venture capital investments – concentrating on enterprises in the medical device space and online internet companies that were beginning to form.

Then came the lifequake: In 2013, Berkman was convicted of financial irregularities around the sale of pre-IPO shares of Facebook and other social media companies and spent the next six years, 2013-2018, in Federal prisons in Estill, SC and Butner, NC.

Berkman, the father of two adult daughters and “papa” to two grandchildren was devastated. “I took full responsibility for my actions, and I paid the price. I moved from one gated community to another. It was tough, but it changed my life – and did so in many positive ways.”

That’s when Berkman described his awakening to the high incidence of incarceration in the US, especially among African-Americans – and to the disturbing problem of recidivism as too many Americans who are sent to prison, serve their time, only to return again after failing to make it on the outside.

Berkman has a good fix on prison reform issues now at the center of his life: “Mass incarcerationand high rates of recidivism are a growing stain on American culture and a waste of human talent – what Herbert Simon calls the ‘ultimate resource’.”

He also has the numbers: “Some 6.6 million people live under supervision of adult correctional authorities – in prisons or jails plus those on probation or parole. This is more than in China and Russia combined. Nearly 2.2 million men and women are behind bars. But here’s the real tragedy: Though more than 600,000 people are released every year, two-thirds will be rearrested within three years.”

Berkman continued, “The cost of incarcerating this many people now exceeds $80 billion a year – not counting the heavy toll this cycle of crime and incarceration takes on individuals, families and communities.”

When I asked him about rehabilitation and job training, I hit another hot spot.

“Rehab has not worked, in part because the strategy of restoring someone to a ‘normal’ situation ignores that too many in the system are under-educated, come from broken families, and grew up with poverty and racial discrimination. These are people, many of them, who have never known a ‘normal’ situation.”

Berkman added, “Effective rehab is hampered by the fact that the last remnants of legal slavery in the US still exist in our prisons.”

“Most Americans are not aware that the 13th Amendment that freed the slaves also has an ‘exception’ clause: ‘Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude,except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction’.”

“It’s very important for Congress and the States to remove this ‘exception’ clause that allows slavery in prisons,´ Berkman said. This is important for symbolic reasons – to move Americans one step closer to achieving the ‘more perfect union’ anticipated by the Preamble to our Constitution.”

“But, more importantly, the ‘exception’ clause is now used as cover to ‘lease’ or otherwise assign prison laborers to agriculture, manufacturing and other for-profit enterprises to do all kinds of things – from producing weapons for the military to sewing garments for Victoria’s Secret – some at ridiculous wage rates, like for 10 cents an hour.”

“These practices have to stop so we can install a skill-development, fair-wage, compensation-based approach to prison labor so those who’ve done their time can succeed in the world of work and in their communities once they are released.”

To achieve this objective – and thereby reduce recidivism – Berkman is advancing what he calls the “PayGoWork-Savings” initiative. PayGoWork will permit convict labor to earn market wages while participating in prison-time apprenticeships and job training focused on a pathway to employment for work-ready convicts as they are released from prison.

The income earned by the convict will be used to (a) partially reimburse taxpayers for a portion of their incarceration costs, (b) pay restitution to crime victims, (c) finance a 401(k)-type nest egg to be recovered at release to help finance a smooth transition to housing and a job, and (d) give the incarcerated hope for the future, thereby increasing the safety and security of the prison setting.

Berkman is devoting his new life and his bonus years to the “Free at Last Coalition” – a non-partisan, non-profit civil rights organization he created in 2018 to garner support to remove the “exception clause” of the 13th Amendment and to advance the “PayGoWork-Savings” reforms.

After a mind-boggling afternoon learning about a part of life outside of my personal experience, I asked Berkman what keeps him going?

“When you live in that other gated community, you realize the value of freedom – and that includes the freedom to order your priorities. Perhaps for the first time in my life, I now have my priorities straight – and that is not just helping others, which I’ve always tried to do – but helping those who are the most vulnerable.”

One-time Notre Dame coach Lou Holtz said, “Life is ten percent what happens to you and ninety percent how you respond to it.” I don’t know if Craig Berkman is a fan of Lou Holtz, but Berkman’s new life, his post-lifequake life, is a living example of the wisdom of Holtz’s observation.

Get the Bonus Years column right to your inbox

We take your inbox seriously. No ads. No appeals. No spam. We provide — and seek from you — original and curated items that make life in the Bonus Years easier to understand and easier to navigate.